The following is a guest article by Frida patron Shelby Perlis.

As Women’s History Month draws to a close, April in Orange County brings a new (if unconventional) opportunity to celebrate femininity. It is no secret that Hayao Miyazaki, director and writer for Studio Ghibli, is a master at crafting films with relatable, admirable girls at his stories’ centers. Miyazaki famously says, “Many of my movies have strong female leads—brave, self-sufficient girls that don’t think twice about fighting for what they believe with all their heart. They’ll need a friend, or a supporter, but never a savior.” From April 1st through 30th, the Frida is hosting Ghibli Fest 2022: featuring 21 animated films which include a plethora of Miyazaki’s fan-favorite protagonists. From a princess who holds her own against evil sky pirates to a girl working to honor her deceased father in post-war Japan, these stories offer relevance and agency to viewers of any age.

My own experience with the Ghibli universe did not begin until I was in college, and in some ways, I am almost grateful for that. By watching these movies as a young adult, I have been able to revel in the nuances and intricacies of their female characters—and recognize what was missing in the films I watched growing up. Here, I am now able to see girls who look like me, who sound and think like me, who are frustrated and restless and underestimated like me… and ones who aren’t like me at all, to my particular delight. Miyazaki makes it clear that feminine power and strength come in many shapes and sizes—and also that power and strength are not required constants in order to be heroic. Perhaps most charmingly, these films do not aim to persuade audiences that girls can be strong or resilient or powerful; even the earlier stories suggest we should be past the need of convincing. Studio Ghibli presents femininity as an inextricable, inexorable cornerstone of a successful narrative. In exploring how the Ghibli girls constitute a unique, well-rounded cast of characters, it becomes even clearer that this April’s festival will be a much-needed treat.

One of Miyazaki’s most beloved female characters is, of course, Chihiro (also called Sen) from Spirited Away. Beginning as a grumpy and unmotivated kid, Chihiro quickly rises to the task of saving herself and her parents from entrapment in a strange world. Even at ten years old, Chihiro is no damsel in distress—managing to satisfy the classic Girl Scout rule of leaving every place better than she finds them. Her bravery helps her brave a monstrous stink-spirit, giant babies, No-Face, cranky witches, and more.

However, she is not always brave. Chihiro cries when her circumstances become overwhelming. She is brash, clumsy, and can be impolite. And she is a role model of femininity just the same. Chihiro’s spiritual journey of growing up reminds viewers that both asking for help and offering help to others are marks of a notable leader.

Shizuku of Whisper of the Heart is a particular favorite of mine. Both a dreamer and a doer, Shizuku takes her love of reading/writing to the next level by aspiring to become a novelist even before high school. Shizuku is not intimidated by Seiji, a provoking boy from school with plans to be a master violin maker. Instead, she takes inspiration from him and concludes that if he can do anything that he decides to do, she can too. Her ambition is infectious for audiences and for her family and girl friends. Being unapologetically artistic, standing up for herself, and drawing inspiration from overlooked places earns Shizuku adoration from her loved ones rather than disapproval—encouraging girls to continually harness the things that make us, us.

As far as ambitious ladies go, Kiki and her delivery service are in a league of their own. Not only does she dive into her training as a witch by beginning a new life in a new city at thirteen, but she navigates her way out of scrapes and stopping points with determined resilience. Kiki is an entrepreneur, a businesswoman, an aviator, an artist, and, perhaps most challengingly, a friend—establishing compassion as a necessary skill for all genders.

Here, she has help. Osono, a pregnant bakery owner, kindly offers Kiki a place to live and forms a deal to kickstart Kiki’s delivery service. Ursula is another role model for Kiki, who helps her regain her confidence in the face of artist’s block. These three women are guiding lights for any audience member (and really, who of us hasn’t had a crush on Ursula at some point?) and remind us that femininity and productivity go hand in hand.

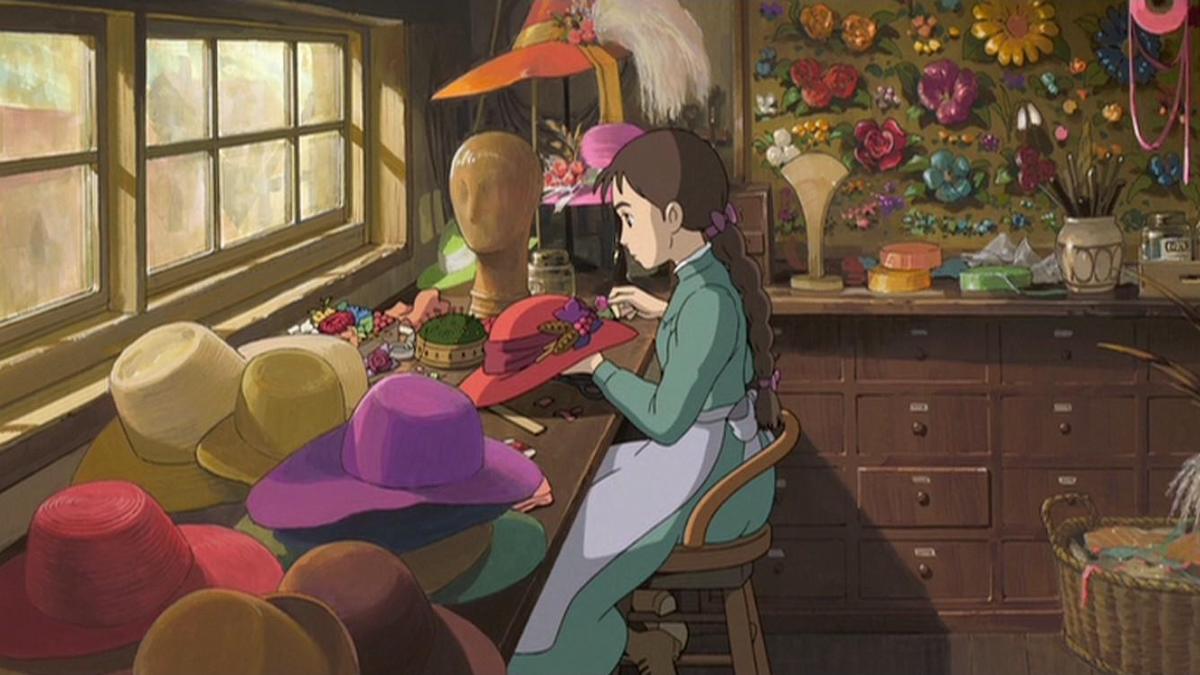

Enduring hit Howl’s Moving Castle offers another enchanting win for compassion. Sophie Hatter is not the expected “strong female character” of her story—she prefers staying in and making hats to going out with friends and is not at all charmed to find herself in a magic castle with a dashing wizard. She is often quiet, and scared probably even more often, and yet she is no less admirable. Sophie and Howl’s Moving Castle prize heart over all else. To those who hurt her, Sophie offers forgiveness and a second chance, even when that person is herself. Sophie honors girls who grow up too quickly and also those who manage to find themselves again through doing the right thing. Notably, characters here (as in other Ghibli films) do not ask her to change—instead, she is celebrated as a deserving and valuable member of her team.

Even when they occupy smaller roles, Ghibli women are foundational. Lin in Spirited Away repeatedly offers Chihiro guidance (even if in the form of snark or sarcasm), and the Wicked Witch of the Waste propels the plot of Howl’s Moving Castle. Women in these films are support systems for their loved ones and communities, are motivators for progress, and are catalysts for change.

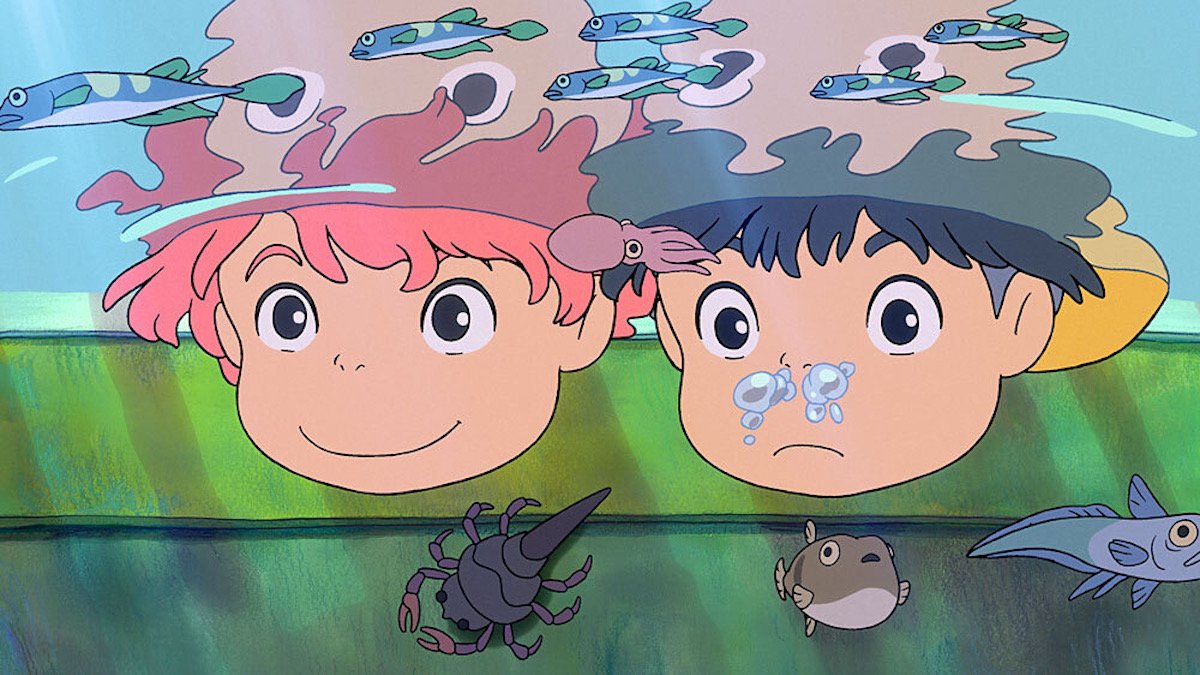

(And speaking of smaller roles—protagonists like Ponyo and Arrietty demonstrate that power can come in any size. Like William Shakespeare said: “Though she be but little, she is fierce.”)

Just as importantly, Miyazaki presents these women as meaningful, often without the necessity of romance. “I’ve become skeptical of the unwritten rule,” says Miyazaki, “that just because a boy and girl appear in the same feature, a romance must ensue. Rather, I want to portray a slightly different relationship, one where the two mutually inspire each other to live—if I’m able to, then perhaps I’ll be closer to portraying a true expression of love.” Love, then, in all its shapes and forms and settings, is not excluded from femininity but rather expanded as an area of opportunity and progress. These women love not only their friends and family but their homes, their talents, their worlds, their powers, their art, and their undiscovered adventures. We—all of us—are better for what we love, Ghibli suggests.

And there is much to love in these films. Here, girls are engineers, farmers, mothers, students, good witches, bad witches, and warriors.

The sea, the air, the fields and forests and frontiers; no space is out of reach for these women. And this month, they aren’t out of reach for us either. Whether feminine or feminist, I hope to see all of you at the festival

Ghibli Fest starts tomorrow at The Frida Cinema with screenings of Spirited Away and Whisper of the Heart and runs through April! Visit our Ghibli Fest page for the complete list of movies and showtimes!