Even in death, it was impossible to escape Jean-Luc Godard at the 60th New York Film Festival this year. The incomparable French New Wave director passed away last month on September 13th at the age of 91, leaving behind boundary-pushing and radical work that will forever color any conversation about the cinematic form. Each of his films, an event – from Berlin to Cannes.

In recognition and in honor of Godard’s passing, the Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center Amphitheater became a sort of dedicated site to pay respects to the late director at the festival. As part of the SPOTLIGHT lineup, the seventy-five-person auditorium played Godard’s exceptional final film, The Image Book, on a loop during the event, offering attendees another glimpse at the film, which first appeared at NYFF56 in 2018.

A press release from the New York Film Festival described the director’s long-standing relationship to its history:

“Godard wasn’t merely a fixture at the New York Film Festival: from its very beginning, Godard’s work has been a guiding light for the festival, with more than 25 films selected across every decade of the festival’s 60-year-existence. (Additionally, he was the subject of an extensive retrospective at NYFF51.)”

Released almost sixty years after his oft-cited first feature, 1960’s Breathless, The Image Book is both a logical extension of Godard’s enigmatic style and a wholly singular piece of filmmaking. Both films deal in the powers (and limits) of cinema as the subject, both are a fleet 90 minutes, but The Image Book arrives after Godard has said adieu to narrative language. He takes up an incredibly freeform process of image-making that both contrives and contradicts meaning. Though not without precedent in his ’60s films (as Richard Brody put it during a panel at NYFF52, “[…] for Godard, things got late early.”), Godard’s late-late period takes the appearance of mixed media collage essays rather than playful Hollywood genre spoofs. What narratives do exist in the more recent work are still overwhelmed with visual experimentation that suggest an artist still searching for new ways of looking, new ways of envisioning the world.

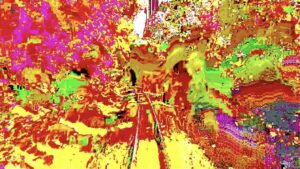

The jump-cuts in Breathless reach their maturation point here in The Image Book, as Godard combines pre-existing film clips with digital video captured on his iPhone to comment on the legacies of cinema history. Collisions of images from the inertia of the first hand-cranked projections. Far from a documentary, The Image Book resembles a paradox for the director whose films are known for their detached dark comedy. Visually, it is very Godardian, but in tone, the film is stunningly humorless. It would be a tough watch if the images weren’t so dazzling. Godard’s manipulation of the footage demonstrates a desire to imagine a new dimension beyond the 3D he worked with in Goodbye to Language. A two-dimensional image that can transport its viewer through space and time; a film that can turn back history.

The unpredictable structure of the film, paired with Godard’s own grave narration, curdles and chills. The feeling of receiving messages from beyond the grave. The tenor of Godard’s voice expresses a clear dissatisfaction if not outright pain at the failures of his revolutionary generation. The establishment powers, in some ways, are more powerful than they ever have been. Can cinema save society? Can its depictions hasten decay, avert destruction? The images Godard conceives appear broadcast straight from doomsday, a suggestion that we’ve already photographed the end – the rest is waiting.

Just as with his debut, The Image Book is also victim to the same lexical gap that divides À bout de souffle (“out-of-breath”) and Breathless. The Image Book’s French title, Le livre d’image, connotes something more age appropriate for a child – think “the picture book” in English. While there might be an ironic twinge in naming a film with such heavy content in it this way, now, after Godard’s death, it rings as far more earnest than before. Godard was the child, not the audience. He is recalling this amalgam of images he encountered in his early years and throughout his life. He is recreating memories as cinema, letting go of the demands of form and working as instinctually as a child would.

As a final work by a capital-A artiste, The Image Book carries a palpable gravitas that, while not as visible as when Godard first made it, is now inescapable when watching. The unique rhythms of the “scenes” have a strange hypnotism that keeps one spellbound and unnerved. Though it may not remain Godard’s absolute last film (the two films Godard was working on at the time of death are rumored to be released posthumously). The Image Book is undoubtedly a standout among this final period. Certainly a standout even among the films at this year’s festival, where fictional narrative cinema is still the primary mode of communication—story as cinema; for Jean-Luc Godard, it was looking as cinema. Cinema as cinema. And now finally, Fin de Cinema.

Adieu language! Adieu Godard!