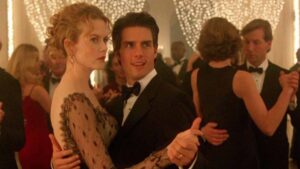

Christmas lights and lavish parties. Bustling city streets and decorations. The masked wealthy and powerful engaged in secret ritualistic orgies held in giant mansions somewhere on the outskirts of a fictional New York City. Eyes Wide Shut may have become an unconventional Christmas film 23 years after its release, but perhaps it was always destined to be.

Famously based on the novella Traumnovelle (Dream Story) by Austrian writer Arthur Schnitzler, which was published in 1926, it follows all the same pertinent plot points of the 1969 Austrian TV movie adaptation of the same name. But if the TV movie is like a used but sensible car, then the Stanley Kubrick adaptation is like a Rolls-Royce in terms of its look and its impeccably photographed mise-en-scène.

But the Austrian television movie directed by Wolfgang Glück was never meant to compete on the same playing field as a movie star-helmed, theatrical, big Hollywood studio release made 30 years later by one of the most acclaimed filmmakers in cinema history. Although Glück’s version was closer to the novella and set in early 20th century Vienna, Kubrick’s was updated to the more modern NYC of the 1990s.

Yet regardless of what you think or hear these days, Eyes Wide Shut wasn’t that beloved by American audiences and critics at the time of its initial release. It may have been met with mixed reviews because there was so much expectation for what a brand-new Stanley Kubrick film might be, especially one that would sadly turn out to be his last. It was better received overseas, in places like Italy, Japan, and Latin America.

But Kubrick, who seemed to redefine a new genre with every film he made, didn’t necessarily ever make the films that people expected him to make.

As Tom Cruise said on Eyes Wide Shut’s initial French press tour about the film not meeting box office expectations in the United States, “The movies, like all Stanley’s movies, they have a life beyond the opening or the first run. You look at Stanley’s movies, they’re for life.” Indeed, one of his most acclaimed films, 2001: A Space Odyssey, wound up in the red upon its initial release.

And Eyes Wide Shut was an interesting concept to launch upon modern American audiences: a slowly meandering art film based on a novella by an Austrian writer from the 1920s, starring the biggest Hollywood power couple of the day.

But it was a long time coming. Kubrick originally obtained the story’s film rights some time after reading the novella in 1968. Since the Austrian television adaptation was released in 1969, one wonders if this helped lead to the delay of Kubrick’s own version. (Some have even gone so far as to suggest that the TV movie subtly influenced some of his other work.)

Having not concluded principal photography on the project until almost three decades later, it seems fitting that Eyes Wide Shut was the final movie in Stanley Kubrick’s career. He had a fatal heart attack in his sleep a mere six days after showing a cut of the film for the first time to Cruise, Kidman, and Warner Bros.

Having not concluded principal photography on the project until almost three decades later, it seems fitting that Eyes Wide Shut was the final movie in Stanley Kubrick’s career. He had a fatal heart attack in his sleep a mere six days after showing a cut of the film for the first time to Cruise, Kidman, and Warner Bros.

Eyes Wide Shut holds the Guinness World Record for longest continuous film shoot, shooting from November 1996 through January 1998 (with reshoots up until June 1998) in what wound up being around 15 months of shooting in total. Kubrick did constant rewrites, and the set was notorious for the amounts of takes he spent on any given scene. (One actress, Vinessa Shaw, who was meant to shoot her scene in two weeks, wound up being there for two months.)

The film was not actually shot in New York City but in a recreation of it built at Pinewood Studios in England (due to Kubrick’s notorious fear of flying), which gives it a further dreamlike quality. While apparently Kubrick went so far as to have the distance between street signs and trashcans measured in the real Greenwich Village, you can still feel on some subliminal level that it’s not actually New York City, especially if you’ve ever spent any time there. But things are often not exactly as they should be when reflected in the mind’s eye of a dream, so in a way, this quality just furthers the film’s themes.

Kubrick also switched the time of year in which the original story takes place from Mardi Gras to Christmastime. It’s indeed difficult to find a scene that doesn’t have a Christmas tree, Christmas lights, or some kind of Christmas decoration in the background. Does all this symbolism connect with the nostalgic promise that the holiday season offers? To hopes and dreams, a feeling of longing that entangles itself here with the fantasy of extramarital desire? Do hazy Christmas lights contribute to the film’s dreamlike quality? People who are acting out unconscious desires are already in a bit of a sleepwalk.

However you choose to interpret it, this makes Eyes Wide Shut (despite its initial July release) sort of a deranged Christmas movie about jealousy and desire (and masked orgies involving the hyper rich and influential). Or perhaps it’s the perfect Christmas movie for those seeking an emotional escape from the cookie-coated good cheer of the holiday fare that’s churned out on repeat this time of year.

I remember my only complaint when seeing this film during its initial release was that every woman in it seemed to have the exact same body type (which is noticeable because it’s a movie that focuses a great deal on women’s unclothed, often faceless, bodies). Knowing Kubrick’s very meticulous attention to detail, this can’t have been accidental. In a story that on its surface is about jealousy and extramarital temptations, perhaps the repeating body type is meant to signify a single, unified type of womanhood that the lead character is being haunted by everywhere he turns. Like a sexual Night of the Living Dead, women popping up to come onto Cruise around every corner, all with the same silhouette. Cruise’s Dr. Harford spends a lot of time wandering through long, eerie nights where people seem either out to have sex with him or out to get him. (After a certain point, are these impulses interchangeable?)

It could be argued that Tom Cruise is at times at his best playing characters who are not entirely likable (his humorous role in Magnolia comes to mind) and his Dr. Bill Harford — wealthy, privileged, with an enormous New York apartment, a gorgeous wife, and women throwing themselves at him left and right — may be another example of this. He does awkward flirting and inserting himself where he doesn’t necessarily belong very well: perhaps both side effects of his character being in a position of privilege.

Cruise has been accused of being flat in his performance in this film — perhaps as juxtaposed with some of his other work. Cruise’s character also has a tendency to repeat the dialogue that was just spoken to him back to the speaker — a conversational style that is reminiscent of the Meisner technique of acting. But this is a style that repeats itself throughout the film, and after 95 takes of any given scene, it’s hard to imagine that anything in this film is unintentional.

Kubrick’s drive towards perfectionism in the form of endless takes (rumors abound that this is the reason Harvey Keitel either quit or was fired from the film and replaced by Sidney Pollack), possibly in an effort to wear down his actors in order to get a more organic performance out of them, leads one to wonder how many other versions of this movie might have existed. In the 1970s, Kubrick was even toying with the idea of making this as a “sex comedy” follow-up to 2001. It’s hard to imagine a ’70s sex comedy version of this film with exquisite cinematography, an obsession with technical perfection, and someone like Steve Martin or Woody Allen in the lead. (Both were considered.) But a very different film that might have been, to say the least.

Kubrick’s drive towards perfectionism in the form of endless takes (rumors abound that this is the reason Harvey Keitel either quit or was fired from the film and replaced by Sidney Pollack), possibly in an effort to wear down his actors in order to get a more organic performance out of them, leads one to wonder how many other versions of this movie might have existed. In the 1970s, Kubrick was even toying with the idea of making this as a “sex comedy” follow-up to 2001. It’s hard to imagine a ’70s sex comedy version of this film with exquisite cinematography, an obsession with technical perfection, and someone like Steve Martin or Woody Allen in the lead. (Both were considered.) But a very different film that might have been, to say the least.

Something about the tone of this movie and your emotional distance from the actors makes you notice the jealous themes and lecherous landscape but not necessarily feel them deeply. Perhaps it’s because Dr. Harford (the name meant to be a play on “Harrison Ford”) doesn’t allow you inside (though you do see flashes of the infidelity that happened in a dream relayed to him by his wife as it continues to linger in his mind).

But even when early on we see a highly emotional woman whose father has just died (and is indeed still in the same room with her) as she tries to make a play for Dr. Harford (as so many female characters in this film do), we aren’t feeling with her. We, as the audience, are disconnected observers. The way she is shot, her emotion seems less meant to transmit and be felt by the audience and more to be externally unsettling and creepy. It’s an interesting experience, and you begin to wonder if a lot of Kubrick’s films contain this cold observational stance: an impeccably shot, sometimes uncanny, sometimes humorous clinical view of the human race without ever having to get too emotionally involved.

Kubrick, whose real-life sense of humor was supposedly dry, seems to convey this through his films in their deadpan matter-of-factness: all of life’s little absurdities and horrors.

We watch Dr. Harford, seemingly in control as far as money and prestige are concerned, yet haplessly stumbling through a greater world he ultimately has no control over. In the same way, we see Ryan O’Neal in Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon stumbling through a lifetime of good and more often bad fortune. Kidman, in contrast, is more vibrant and multilayered here than the male lead in either film (while juggling continuous nude scenes and an accent that isn’t even her own.) She’s exquisite, and her emotional range is almost eerie, but perhaps something closer to a blank canvas is what Kubrick preferred more for his leading men in these two films about men being pulled by tides that are ultimately beyond their control.

Kubrick himself avoided interviews and hated having to explain his intentions, letting his films ultimately speak for themselves. But like with anything, I think the way to get the best of this film is to approach it without any expectation and on its own merits. Probably something that was impossible to do at the time of its initial release but perhaps easier to do looking back at it now through the kaleidoscope of time

Eyes Wide Shut screens starting Thursday, December 1st.

Thursday, Dec 1 – 7;15pm

Friday, Dec 2 – 7pm

Tickets