It is often said that there is no stronger way to learn something than to fail at it. What doesn’t come about as often is what it even means to fail at something. The notion’s as subjective as it is to have succeeded. Truth be told, it’s really all a matter of what is dictated not just by those around you but also eventually yourself as to what is considered a true failure. In Michael Cimino’s case, however, failure was enough to be slandered and slaughtered by the world at large and to simply, and somewhat cruelly, never find the success you once reaped again. It was 1980 when Cimino’s monolithic, deeply American epic, Heaven’s Gate, premiered amongst a hurricane of bad press and desperately shortened cuts in order to simmer down its 219-minute final cut to a more palatable runtime.

The term “disaster” was marked upon its release from the moment that Cimino was reported to not only have been already five days behind schedule on-set within its first week of shooting but also to have adopted an allegedly despot-like mannerism as director, demanding the carte blanche that was given with the project at every which way, ballooning the budget to a then-unprecedented $44 million ($170,261,643 when adjusted for inflation). As I write this out, the film’s total gross since its release was $3.5 million. It’s difficult not to feel as if Cimino was doomed from a very early point to have these results, and it’s even more so to consider how a film like Heaven’s Gate — one imbued with one of the most overwhelming canvases in cinema at large and firmly amongst the likes of Frederick Wiseman’s Welfare as one of the greatest films ever made about America — caused the demise of New Hollywood auteurism in favor of the high concept tentpoles that Spielberg and Lucas pioneered, when the alternate reality in which it was recognized as the radically culture-shifting, absolute apex of studio filmmaking’s capabilities is perhaps the one that should have been.

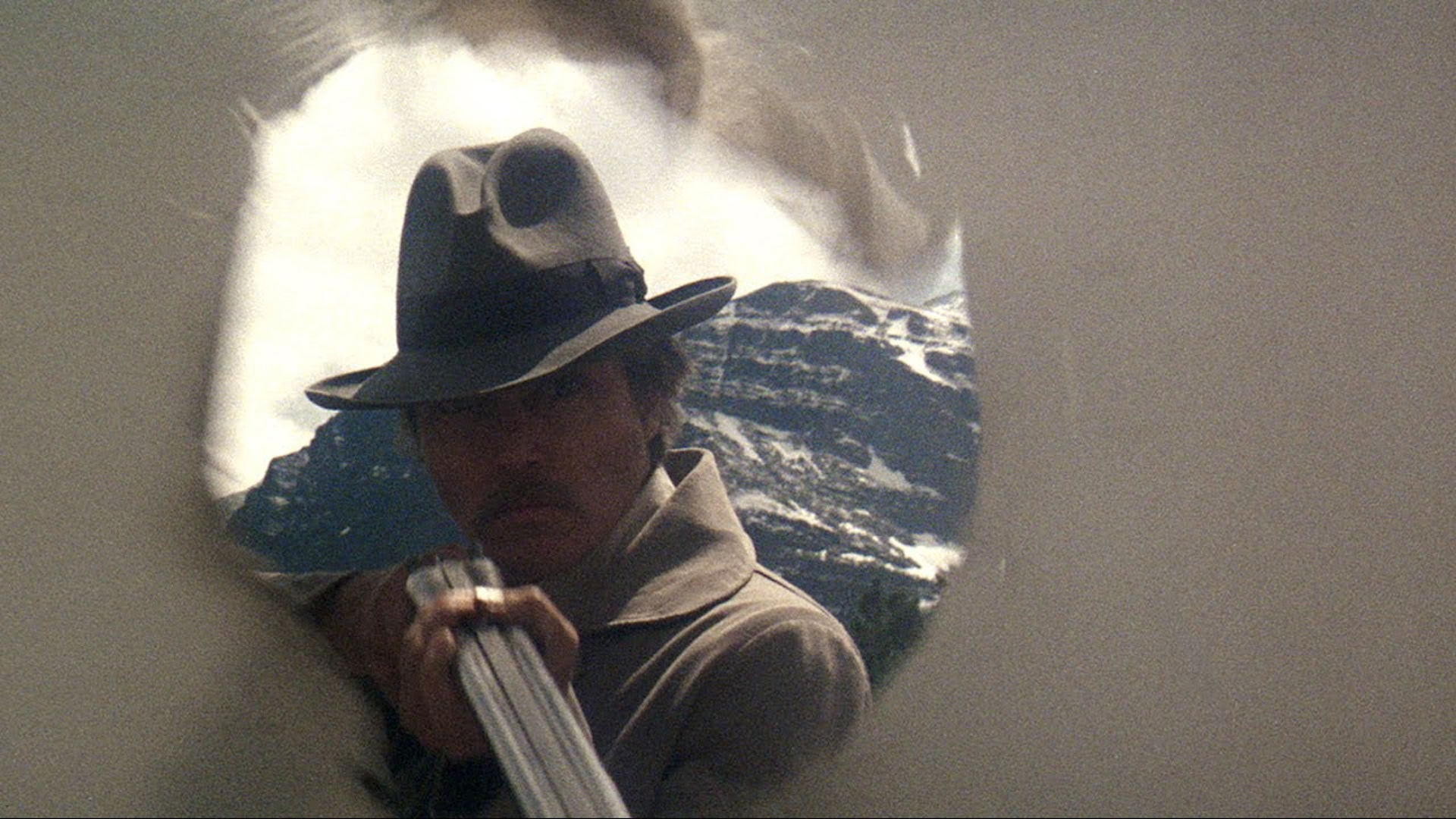

So why pick the film to play for my birthday month? Why not, based on what I’ve already said about it? Where else do I even begin, besides elaborating even more on its sheer magnitude? Cimino’s film is not just begging to be gazed upon, rather it stomps down your door to escape the confines of basic narrative filmmaking, leaving behind a trail of flame. It is a film of mighty rage and yet the most tender mourning. If you were to encapsulate the human experience via film, you’d be hard-pressed not to account for the entirety of such an overwhelmingly beautiful production. It at once both celebrates and damns the pains and intimacies that are innate with being alive in a country where your freedom has no choice but to slowly diminish. Not unlike the tired, aging soul of Johnson County marshal (and former idealist) Jim Averill (Kris Kristofferson), whose overhearing of the Wyoming Stock Association’s plans in 1890 to eliminate 120 European emigrants for alleged cattle rustling surely puts the story into further motion but not before much of its runtime is devoted to Cimino’s remarkably immersive atmosphere and storytelling, including the love triangle between Averill, brothel-owner Ella Watson (Isabelle Huppert), and bounty hunter Nate Champion (Christopher Walken), as well as an extended (to say the least) opening sequence set during a Harvard graduation ceremony ten years prior that unwaveringly pushes the wealth-born Averill and his friend Billy Irvine (John Hurt) out into the cruelty of a nation awash in xenophobia and wayward policies that saw the brutal mistreatment of knowingly innocent lives.

The film’s fury is only matched by its ability to preserve the leisurely quality of its so-called indulgences, which is supplemented by the mammoth 219-minute runtime of its final, Cimino-approved cut. But what critics and filmgoers have spent years dismissing as self-indulgence, I personally can’t see as anything besides the most necessary of world-crafting within a scope-framed canvas that was miraculously allowed to be visualized so expansively. The audacity of said canvas coalesces in the titular sequence — set during a joyous occasion shared among a majority of the characters at a roller-skating rink called Heaven’s Gate, in which there isn’t a frown to be found. It is a ravishing sequence that reveals its magnitude to be more akin to a microcosm. In a world that wants you constricted, and if not constricted then dead, a communion of townsfolk sharing a collectively euphoric experience is made to feel just as radically charged as Nate Champion saying “fuck the President.” Cimino provides masterful harmony between sensitivity and anger to create seemingly the ultimate vision of a genuine long-lost time, recreated with the kind of painstaking detail that could only be realized with its budget, at last giving into its own anger once tragedy begins to materialize. As the tagline on the film’s poster states, “What one loves about life are the things that fade,” which is what simultaneously acts as the film’s thesis, creating a relentless, bitter temporality through the things and people not meant to last in the death-driving system of the American West.

The film’s fury is only matched by its ability to preserve the leisurely quality of its so-called indulgences, which is supplemented by the mammoth 219-minute runtime of its final, Cimino-approved cut. But what critics and filmgoers have spent years dismissing as self-indulgence, I personally can’t see as anything besides the most necessary of world-crafting within a scope-framed canvas that was miraculously allowed to be visualized so expansively. The audacity of said canvas coalesces in the titular sequence — set during a joyous occasion shared among a majority of the characters at a roller-skating rink called Heaven’s Gate, in which there isn’t a frown to be found. It is a ravishing sequence that reveals its magnitude to be more akin to a microcosm. In a world that wants you constricted, and if not constricted then dead, a communion of townsfolk sharing a collectively euphoric experience is made to feel just as radically charged as Nate Champion saying “fuck the President.” Cimino provides masterful harmony between sensitivity and anger to create seemingly the ultimate vision of a genuine long-lost time, recreated with the kind of painstaking detail that could only be realized with its budget, at last giving into its own anger once tragedy begins to materialize. As the tagline on the film’s poster states, “What one loves about life are the things that fade,” which is what simultaneously acts as the film’s thesis, creating a relentless, bitter temporality through the things and people not meant to last in the death-driving system of the American West.

It is this notion that also happens to bleed over into Cimino’s personal history, as well as her later years. Detailed in Charles Elton’s biography, Cimino: The Deer Hunter, Heaven’s Gate, and the Price of a Vision, Cimino began to present herself as a woman in the 1990s, oft being referred to as “Nikki” by her friend and personal cosmetologist Valerie Driscoll. As her identity became more fluid over the years, Cimino’s penchant for secrecy intensified following the public outcry of Heaven’s Gate as well as her inability to build on the success that she had mined in her 1978 Best Picture winner, The Deer Hunter. But for as much responsibility as I feel to dictate my personal feelings based on whatever’s considered factual, the notion that Heaven’s Gate was the byproduct of a trans woman’s vision can’t help but feel like the secret weapon to truly understanding its wavelength. In a country that has thrived off the backs of the marginalized, and to no coincidence has been the location of decades of murders of trans people, there’s little to no surprise that a film as angry and unwilling to compromise as Heaven’s Gate, in spite of various efforts to have it reincarnate through shortened cuts and eventually the surfacing of its final cut, feels like a miracle in both studio filmmaking and cinematic expression.

What has spent decades being lamented as the death rattle of New Hollywood may have, in actuality, resulted in something akin to a vicious wildfire, spreading to United Artists without remorse and bringing down the entirety of Hollywood with it, only for it to resurface in its opening stage as a sanitized, franchising husk. There’s no doubt in my mind that a film as important as Heaven’s Gate can only be one that resulted in the transformation of the system it was produced in and is one that will always exist as a condemnation of the systems that defined America’s yesteryear. With a $44 million price tag, Michael Cimino proved that the only way to depict bigotry, slaughter, and trauma is to set it up in smoke and rely only on hope that the future of American cinema will be allowed into far more open doors than its past ever was. There’s only one more thing that Heaven’s Gate can be referred to in its entirety — a hurricane, and a necessary one.

Heaven’s Gate: Director’s Cut screens starting Friday, August 18th.

Friday, Aug 18th – 2:30pm

Sunday, Aug 20th – 6pm

Monday, Aug 21st – 7pm

Tickets