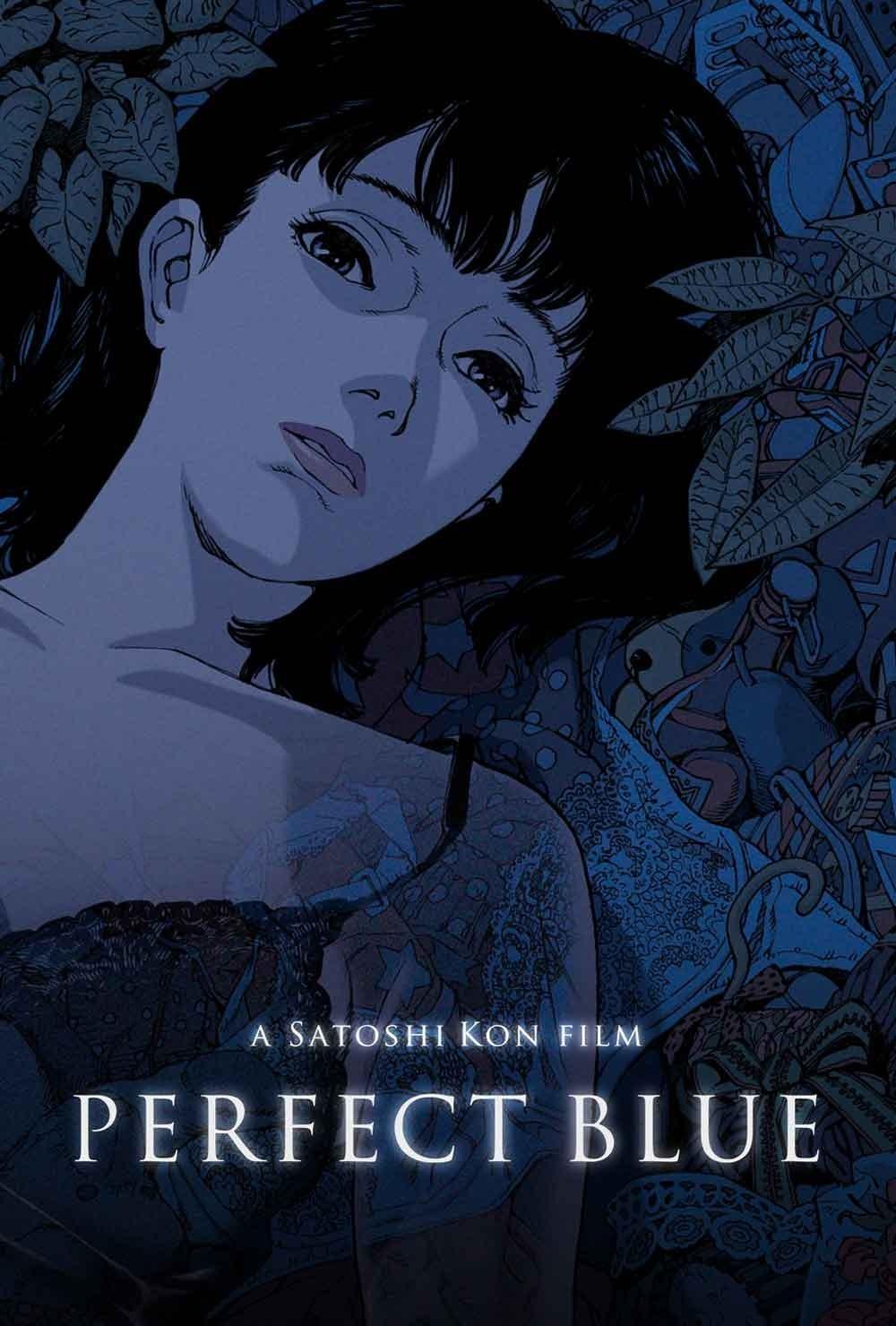

Perfect Blue

The Frida Cinema's seating is first-come, first-serve. For our Midnight Screenings, please plan on arriving by 11:30pm to ensure ample time for parking, picking up concessions, and securing optimal seats. Screening will begin promptly at midnight.

Director: Satoshi Kon Run Time: 82 min. Release Year: 1998 Language: Japanese

Starring: Junko Iwao, Masaaki Okura, Rica Matsumoto, Shiho Niiyama, Shinpachi Tsuji

Master animator Satoshi Kon’s masterpiece, Perfect Blue, returns to The Frida’s screen for some well-deserved encores! If you missed it the first time around, come see this amazing restoration from our friends at GKIDS on the big screen!

Former pop idol Mima Kirigoe (voiced by Junko Iwao) leaves her idol group to pursue acting. But as she trades microphones for movie sets, the lines between her past and present blur: a mysterious website chronicling her every move appears, an obsessed fan creeps closer, and the roles she plays begin to swallow who she thought she was. The camera follows Mima into a mirror-maze of perception and performance, where even the reflection cannot be trusted.

Rich with acute unease, Perfect Blue remains a landmark of adult animation—its influence stretching from horror to cinema and animation alike. With every cut-frame and every whispered echo, it undermines the fantasy of stardom and forces the audience to ask: Who am I when they’re watching?