“The film is a bit more epic in scale than what it seems on the outside…It’s a bit like songs on an album, they are short stories that mean something in the bigger picture.”

– Joachim Trier

In a superlative year for font aficionados, the cinema of 2021 has revealed itself to be the Year of the Picaresque: films telling one story, with built in act breaks signaled by an intertitle. Not just for the literary crowd, this structural device can be seen across the full spectrum of movie genres this year, from blockbusters to indies, which begs the question of the form’s appeal in the current moment. By now, streaming services (and social media et al) have eviscerated any traditional notions of content length, as their programming does not rely on public broadcast or exhibition constraints; where the half hour program had been the gold standard since the dawn of Television, shows on streaming services freely run anywhere from 15 to upwards of 39 minute episodes as desired by the creators. Yet this appetite for modular length TV has not yet translated into an appetite for longer films – increasingly, the films are emulating television.

This was certainly the case in Michael Sarnoski’s debut feature Pig, a summer indie that plated its story about food and grief like a three-course meal: ‘Rustic Mushroom Tart’, ‘Mom’s French Toast and Deconstructed Scallop’, ‘A Bird, a Bottle, and a Salted Baguette’; Oscar frontrunner Jane Campion meanwhile, worked directly from a literary source material, adapting The Power Of The Dog into a film composed of five untitled acts; Even the colossal 4-hour Zack Snyder cut of Justice League got the chapter film treatment this year, with six acts plus an epilogue: ‘Don’t Count on It, Batman’, ‘The Age of Heroes’, ‘Beloved Mother, Beloved Son’, ‘Change Machine’, ‘All the King’s Horses’, ‘Something Darker’, ‘A Father Twice Over’.

But the cinematic picaros in those films pale in comparison to the capricious young woman at the center of Joachim Trier’s mordantly titled new film, The Worst Person In The World (now playing at The Frida Cinema). Portrayed with thoughtful care by Renate Reinsve, Julie is the titular worst person in the world of her modern Norwegian life – privileged, yet imperfect. Her millennial malaise plays out in an audacious, nearly epic, fashion, as the film traverses several years of Julie’s life across twelve episodes – the most out of all the other films mentioned – plus a prologue and epilogue.

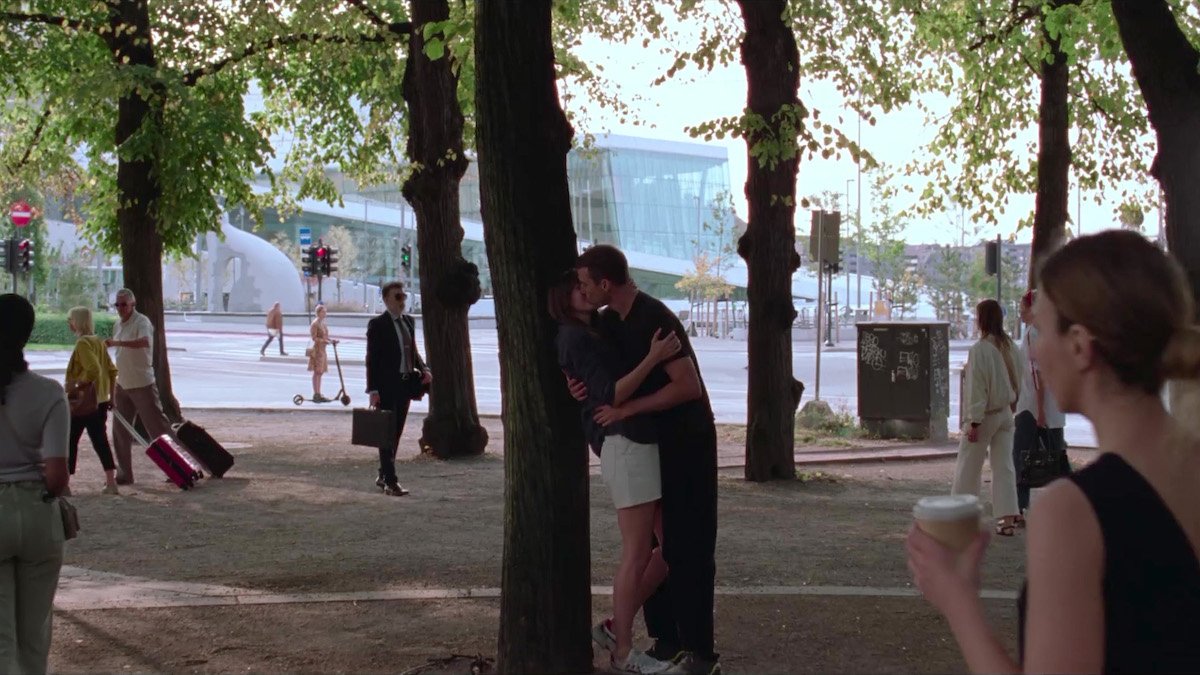

The film’s primary dramatic engine is powered by the earnest momentum of youth, as twentysomething Julie’s carefree attitude propels her through all manner of growing pains, and quarter life crises on her way to middle age. Trier and co writer Eskil Vogt tease out this transcendent journey with the lilt and energy of a musical, contrasting the romantic promise of cinema with a story about stagnated, or stagnating, characters. This extends to Julie’s out of touch family who have trouble supporting her beyond financial means (and even then…), as well as the two men she inadvertently forms a love triangle with: Aksel and Eivind.

Though separated by age and ambition, Julie, Aksel, & Eivind represent a continuum of people on a plateau, glimpses at different states of calcification brought on by the weariness of aging. Reinsve does most of the heavy lifting here, effortlessly disguising Julie’s inconsistency as whimsy, and her selfishness as relatable while she tinkers with her personality during this part of her life. The similarly aged Eivind (Herbert Nordrum) appears genuinely content with his station in life, if a bit static. Courted by numerous critics awards for his performance as Aksel, Anders Danielsen Lie provides brilliant foil to Julie as a similarly anxious “worst person”, fifteen years her senior. A relatively successful comic book writer, Aksel still struggles, like Julie, to know whether or not he’s wasted his time, a question that reiterates itself throughout the film with a biologic urgency.

The Worst Person In The World’s Best Original Screenplay nomination at the Academy Awards anoints the film as one of richly scripted characterizations and situations, but ignores the breathtaking image making that sustains the film. Trier and cinematographer Kasper Tuxen make dynamic compositions with saturated colors that illustrate a grand, exciting world, inviting Julie to join it. Even when the film shifts into its contemplative third act, the visual palette never falters, affirming the lust of life, no matter one’s age.

Despite their structural resemblance to television, ‘chapter films’ like The Worst Person In the World derive as much of their cinematic power from the offscreen events as they do from the onscreen ones, gesturing at oceanic depths of emotion existing beyond the boundaries of the frame. Whether it’s the geographic stasis of the American western frontier, or the debilitating vastness of your thirties, the foregrounding of the passage of time in these films heighten even minor beats into grand, dramatic stakes. For characters like Julie, each of these moments, micro and macro, align like waypoints on the path to wisdom in a life fully lived. Epochs contained in every episode.

The Worst Person in The World screens this week and next at The Frida Cinema.

Monday, Feb 28 – 5:30pm, 8:15pm

Tuesday, Mar 1 – 5:30pm, 8:15pm

Wednesday, Mar 2 – 5:30pm, 8:15pm

Thursday, Mar 3 – 5:30pm, 8:15pm

Friday, Mar 4 – 2:15pm. 5pm

Saturday, Mar 5 – 2:15pm, 5pm

Sunday, Mar 6 – 2:15pm, 5pm

Monday, Mar 7 – 5pm

Tuesday, Mar 8 – 5pm

Wednesday, Mar 9 – 5pm

Thursday, Mar 10 – 5pm

Tickets