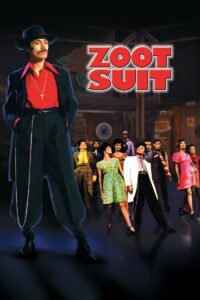

The groundbreaking film Zoot Suit is one of the most significant Latino films in American cinematic history. Brought to life by director and writer Luis Valdez, Zoot Suit combines two major events in 1940s Chicano (Mexican-American) history, the Sleepy Lagoon murder, and the Zoot Suit Riots, to highlight the monumental significance these events had on the early Civil Rights Movement, through the eyes of the Chicano experience.

The groundbreaking film Zoot Suit is one of the most significant Latino films in American cinematic history. Brought to life by director and writer Luis Valdez, Zoot Suit combines two major events in 1940s Chicano (Mexican-American) history, the Sleepy Lagoon murder, and the Zoot Suit Riots, to highlight the monumental significance these events had on the early Civil Rights Movement, through the eyes of the Chicano experience.

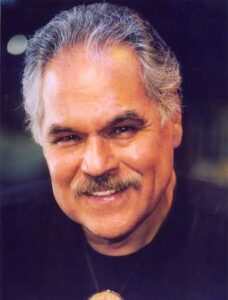

Valdez, who’s regarded as “The Father of Chicano Theatre”, is the most influential Chicano director of American cinematic history. He’s also a renowned award-winning playwright, actor, political activist, author (Theatre of the Sphere: The Vibrant Being), and founder of the El Teatro Campesino theatre, in San Juan Bautista, California.

In 2015, Valdez was awarded The National Medal of Arts by President Barack Obama, for, “Bringing Chicano culture to American drama. As a playwright, actor, writer, and director, he illuminates the human spirit in the face of social injustice through award-winning stage, film, and television productions”.

Zoot Suit follows a young pachuco (a Chicano of the zoot suit counterculture) Henry Reyna, based on the real-life Henry Leyvas and his conscience El Pachuco. As Henry and his friends face a severely biased and racist legal process when they are wrongfully accused and convicted in the Sleepy Lagoon murder. As Henry faces his fate, he’s forced to reexamine who he is and what it means to be Chicano.

In remembrance of the 80th anniversary of the Sleepy Lagoon case, Valdez, in this extensive interview, shares with us his early interest in the theatre, the creation of Zoot Suit, its impact, and the importance of honoring Chicano culture.

The Early Years and the Pachuco Influence:

Justina Bonilla: I understand you have a connection to Orange County.

Luis Valdez: I used to have a Tio and Tia from Santa Ana. Santa Ana was a very important place. I know how important it was for farm workers. I’m very aware of its history.

How did your love for the theater begin?

It’s been a lifelong obsession. I got hooked, when I was six years old, in 1946. We were on the migrant path with my migrant farm worker parents. I went to school not knowing how long I was going to be there.

My teacher took my little lunch bag, a little brown paper bag my mother used to put the tacos in and to make a paper mache mask. It really astonished me that you can take paper and turn it into a mask. Since it was already November, I figured this couldn’t be for Halloween. I asked, “What’s this for?” She explained, “It’s for a play. The whole school’s involved, and we need first graders to play monkeys. It’s called Christmas in the Jungle.”

I forgave her about the bag. Then, I auditioned and got my first role. I was so happy. I was on top of the world. It was my debut. I loved everything about it.

The week of the show, we were evicted from the labor camp, where we were staying because we were migrant farm workers. I got home, my mom told me, “We’re leaving tomorrow.” And I said, “But Mom, the play is on Friday.” She explained, “I know but we’re being evicted.” We were evicted from the labor camp and I was never in the play.

I’ll never forget driving through the town at the crack of dawn, in the San Joaquin Valley fog. I felt a great big hole open up in my chest. But I took with me the secret of paper mache, the unresolved desire to do theater, and anger because we’ve been evicted.

Approximately 20 years later, I went to Cesar Chavez and pitched him an idea for a theater by and for farm workers. So there’s the complete circle. That’s how I got hooked on theater. But also at the same time, I got hooked on community activism, on trying to do something for Campesinos (Spanish for farm laborers).

What inspired you to write the Zoot Suit play?

Well, I’m old enough to remember the pachucos. I was born in 1940. So the pachucos were around when I was a kid, in the mid and late 40s. In Delano, where I was born and raised, there was a concentration of pachucos on the weekends. They’d come into Chinatown. One of them happened to be Billy Miranda, my older cousin, the oldest of the grandchildren. He was a pachuco by sixteen years old and had a running partner called CC. They used to hang out together, with CC’s brother Rookie.

CC later went to the Navy and came back. He was instrumental in desegregating the Delano theater. In those days Mexicans, Blacks, and Filipinos couldn’t sit in the orchestra section, we had to sit on the sides. Since he had been in the Navy, CC figured he would sit in the orchestra section, with his date, who later became his wife. The manager came and tried to get him to get up. When he didn’t get up, they called the police, and they took him away.

Everybody thought CC was in real trouble. But there was no law that said you couldn’t sit in the orchestra section. They had to release him and tried to intimidate him. Then, all his friends saw that he got away with it. The next weekend, everybody went to the movies and sat in the middle section. They desegregated the Delano Theater. I remember that. I saw that happen. And it happened because of a pachuco.

Years later, when I was on my way back to Delano, I was asked, “Are you going to go work with CC?” I was surprised, “CC? That guy’s still around?” They told me, “Don’t you know who CC is? He’s Cesar Chavez.” So, this pachuco that I knew as a kid became Cesar Chavez and his brother Rookie became Richard Chaves. I meet Cesar when I was six when he was a pachuco.

My cousin Billy did not survive the 50s. He was killed at the age of twenty-three, with seventeen knife wounds to the chest, in Phoenix, Arizona. He died a violent pachuco death, but he was a sweetheart. He wasn’t violent. He was quite the contrary, he was a gentleman. But in any case, when I wrote Zoot Suit, I dedicated it to the memory of my cousin Billy.

When I went to work with Cesar that’s the bond that we had in common, that Billy had been my cousin. And that I had known about Cesar when I was a little kid. So all of that connects right back to the pachuco.

Where did the pachuco culture originate?

They say it came from back east, in Georgia, and Harlem, before it came west. It passed through El Paso, and the zoot suiters picked up the name “El Pachuco”, out of el pachuco dejas which is El Paso, Texas.

In Los Angeles all the pachucos here we called Califas, until there was a big confrontation with the pachucos that were coming in on trains into LA, and settling in LA. The big confrontation led to them being called pachucos. This was about 1940/1941. It’s a story of Los Angeles. The pachuco experience is part of the history of LA and the whole country.

What impact did music have on pachuco culture?

There’s no way that you can really deal with the pachuco experience without the music. The music is what defined the zoot suit. It’s the jazz era. It’s the swing era. And so by the late 1930s, the zoot suit evolved in the dance halls.

The Mexican parents weren’t so much into swing music and jazz, as the pachucos were. They were they were Americans. They were Americanizing in this very special West Coast and L.A. kind of way. L.A. was launching a lot of the stars, like Benny Goodman and later Fats Domino. A lot of people came to L.A. because it was a population here, largely Chicano that was very receptive to their music, to rhythm and blues.

How did pachucos deal with the challenge of assimilating to American society, while maintaining their cultural identity?

There are different ways to be assimilated, but it’s a process of acculturation. To be acculturated means that you get used to the culture in a sense. You can be acculturated as an American, but remain Mexican, Filipino, or Japanese. You retain the original culture without diluting it, but you become fully American at the same time. That’s the experience of today. People didn’t feel that way back in the day. You are either American or you were an immigrant.

The fact is, the Chicanos were instrumental, the pachucos in particular, in establishing a new way to be in the United States. It’s a multicultural profile. They loved American music. They were bilingual. They spoke English and played with the language. The word zoot suit itself is one of those strange words that seems to have no source. So is the word pachuco. No one knows really where the word pachuco came from, or even some of the pachuco slang. Some of it came from Mexico City. It’s more of a multicultural appreciation of the world.

The Chicano pachucos were adapting and accepting African American culture. It was happening in L.A. For example, the whole growth of Protestantism among Mexican Americans is part of the same phenomenon. Its exposure to African American church traditions, particularly the Baptist Church. A lot of Mexicans became Baptists. What they were doing is acculturating to an African American reality.

This is part of the American process. One of the things that happen in this country is that all the cultures of the world get exposed to each other in a very direct and intimate way. So it’s no surprise that very young people begin to absorb cross-cultural influences, then adapt and create new identities. The pachuco experience was very much a part of that.

However, this did not include the original Chicanos, who were the immigrants that came from Mexico, to work in the fields, like Henry Leyvas’ parents. His father, Don Severino, had fought in the Mexican Revolution, with Pancho Villa. He was very proud of that and still talked about that. But, once he came to California, that was all over. He was a farmworker here and not a revolutionary. Dolores, the mother, was amazing. She was the mother of about a dozen children, who always stood her ground. So that was that other generation.

Social Unrest and the Zoot Suit Play:

With the storyline of the play intertwining the Sleepy Lagoon murder and the Zoot Suit Riots, how essential was it for the story to include both of those events?

In my original draft, I included the Japanese being taken away in the spring of 1942, which set up the atmosphere in LA that led to the Sleepy Lagoon case and the Zoot Suit Riots. It was this increase in racism and racist attacks on the West Coast, due to many things.

L.A. changed dramatically during World War II. It became a war production center. There were factories and jobs. So, people poured in. African Americans from the south poured into L.A. and Mexicans kept coming. A lot of them used it as an opportunity to get out of the fields and into factories, which was really important. Many of them were women. Rosie the Riveter was originally Rosita the Riveter, she was a Chicana from San Diego. But in any case, there was a lot of resentment from racists that didn’t like this change. That set up a real stew in Los Angeles.

The Sleepy Lagoon murder became the opening shot. After the Japanese were taken out, then the law turned off all their eyes and lenses onto the pachucos in the streets. They singled out the 38th Street gang, which was more of a boys’ club than a gang. It was a hangout for guys and girls. But the fact that this led to the sensational trial, about the death of a guy at the Sleepy Lagoon.

What was the Sleepy Lagoon murder?

The Sleepy Lagoon was an old reservoir outside of what was at the time the LA city limits. It’s now the City of Commerce. It was a reservoir out in the country. The Chicanos and Chicanas used to use it as a lover’s lane. The kids would swim there. That lead to gang fights over the place. Then, one night, a kid was left dead out there.

The law rounded up the whole 38th Street gang and blamed them for the death at the Sleepy Lagoon, which was all circumstantial. Nothing was proven.

How did the trial impact the 38th Street gang?

It was a mass trial. That’s racist to begin with because everyone’s entitled to an individual trial. Two of the twenty-four guys who were originally arrested demanded to have original trials. They were never part of the twenty-two that actually went on trial.

These young guys didn’t know what their rights were. So, they were all put on trial. Twelve were found guilty of first and second-degree murder. The twelve were sent to San Quentin. Four for life. It was ridiculous. They ended up spending two years in prison, while the Sleepy Lagoon appeal was happening. That eventually was successful. Between 1942 and 1944 they were released.

What were the Zoot Suit Riots?

In the summer of 1943, in L.A., Servicemen, sailors mostly, attacked pachucos, stripping their suits from their bodies, out in the streets, and left them naked and wounded.

How did the Sleepy Lagoon Murder and Zoot Suit Riots impact the L.A. community?

It left a psychic scar in LA. When the Zoot Suit play came out, the older people came to see it as a way of remembering that this had in fact happened and to heal. It’s a notorious part of LA history. In many ways, it’s the opening shot of the second half of the 20th century and the racism that followed, which led to the Chicano movement and to the civil rights movement. It’s an important case and they’re tied in together.

For the story, how essential was it to tell it through the pachuco perspective?

If I had written it from a psychologist’s point of view, or a cop’s point of view, I would have concentrated on the criminal element, which is what the stereotype does. So why condemn the pachucos for being human? Give them the full display of their potential and who they are.

How did meeting Henry Leyvas’ family influence the play?

I first met Alice McGrath, who was the secretary of the Sleepy Lagoon Defense Committee and later became the Alice in the play. I met her through Carey McWilliams, who was the Dean of American Sociologists. Alice then introduced me to Henry’s family. I got to meet Henry’s mother, father, sisters, and brothers. His father was dying of cancer. I saw that it was a normal, good-looking family. But they were definitely Chicanos from East LA. As a result of that, my focus on the story became not just on Henry, but also on Henry and his family.

Were you able to speak with any of the young men involved?

When I initially set out to try to talk to the guys, none of them would talk to me. They didn’t want to talk about the case. But once I had written Zoot Suit and the play had been performed once, the guys started to come out of the woodwork. Before we had the film contract, I had an individual contract with all of them to tell their story. And finally, I negotiated the collective story of the 38th Street gang.

How did audiences react to the Zoot Suit play?

A million people saw the play at the Mark Taper Forum in L.A. and then later in Hollywood at the Aquarius Theatre. Half a million people saw the play, at 1,200 people a night at the Aquarius theater. That went on for a year.

Zoot Suit is considered the first Chicano play on Broadway. How does that make you feel, to be able to break new ground into mainstream American theater?

I’m very proud of the fact that we finally got there. That a Chicano play made it to Broadway. There haven’t been too many Latino plays in general. We now have Hamilton, by Lin-Manuel Miranda, which is great. But the fact is Hamilton is about people of color playing white people. We need our stories to be on the stage, being played by ourselves.

One of the things that I’ve always felt in my work in the theater, is that Latinos should have arrived in New York in the 1930s, with everybody else. Like the unions, farmworkers should have been unionized in the 1930s with everyone else, but they weren’t. They and black people were excluded because of racism.

Black people in unions and in the theater had to wait for another twenty years before they got their dues. Raisin in the Sun was the first modern African American play to really break ground on Broadway. Lorraine Hansberry’s play started the whole African American cultural change, that lead to where it is today.

Twenty years after that, Zoot Suit arrived. It was finally the Latinos or the Mexican Americans making it to the great white way. But not without tremendous blockages, reactions, resistance on the part of critics, and even on the part of some of the general public from the Midwest, for instance, that weren’t ready for it. But it did break ground. I felt that and understood that politically because I’ve always been a community organizer.

But at the same time, as an American artist, I figured that we deserved a chance to have those doors open to us, especially from the West Coast. That’s still not happening to any great degree. It’s still a struggle that needs to be done. And as far as I’m concerned, the only way to do that is by standing up for our pride and standing up for our own history. Zoot Suit continues to do that.

The Zoot Suit Movie:

What led to the decision to take Zoot Suit from the stage to the screen?

My original intention was to create Zoot Suit as a play. When there was an opportunity to go to New York we went there. After that, we turned our interest to make the film.

I had a concept for the film with special effects that never got made, because a $20 million movie was too much for a first-time director. I shopped it around to the studios, nobody would bite. I was told it can’t be done.

People tried to buy the rights to Zoot Suit. I was offered half a million dollars for the rights of the play. I decided that I wanted to retain the rights to write and direct Zoot Suit. Eventually, Ned Tannen, who was the president of Universal Studios, gave me a chance to film it.

With a 1.2-million-dollar budget. We had thirteen days to shoot the movie. We shot it at the Aquarius Theater. I shot Zoot Suit as a combination film as a play within the film, within a play. It was a concept that I thought would preserve the play, but at the same time, turn it into a movie. To bring it to a wider audience. After 40 years we’re still going.

How did you decide on which artist to use for the film’s soundtrack?

I had the music of Lalo Guerrero, who’s “The Godfather of Chicano Music”. Lalo had an orchestra in the 1940s. He wrote five of the numbers that are used in the play. I just incorporated them and use them to motivate the scenes, with his permission. It turns out that Lalo was my dad’s cousin.

While the major music numbers are Lalo’s, we also had incidental music that was sourced directly from original sources, like The Andrew Sisters. We incorporated other classics, like “Two o’clock Jump”.

Charlie Rogers, who worked with my brother Daniel on the music for the movie, also reorchestrated the musical numbers to include more than 40s sound. Even “Zoot Suit”, which is the key song in the opening is based on, “Oh Babe!” by Louis Prima. It has many roots, going way back into the period.

What led to the decision to have Henry as the main character of the story?

The newspapers pretty much blamed Henry, as the leader of the gang. He was sensational. If you look into his story there’s a lot of personal evidence to testify that he was in fact, the leader of this group. He was pretty intense. What amazes me, is that to this day is that you can see in photographs his composure. He was very cool under pressure and very defiant at the same time. The cops hated Henry.

How was Edward James Olmos chosen to play El Pachuco?

Eddie came to us through the audition process. He’d been acting but was a musician and rock and roll singer. He didn’t come to our audition deliberately but had other business at the Mark Taper Forum when we were having auditions.

My brother Daniel, saw Eddie in the halls and asked him, “Did you come to audition?” And Eddie replied, “For what?” After Daniel finally got him to audition, I saw him eventually, and we knew that he was perfect. He was the right face. That face was amazing.

Eddie was quite an actor. He could move, sing, and dance. It was a lucky accident that we found him. It was also a lucky accident for him because it was the start of his career as a movie star.

What does El Pachuco represent within Zoot Suit?

He represents a consciousness. There has to be a point of view. Zoot Suit was being told from the point of view of the pachuco, who is larger than life. It’s symbolic, and not too many people know this, but he is a reincarnation of the Aztec god of street knowledge, Tezcatlipoca. And as the Mayans described him, the jaguar night sun. He’s the hero of the subconscious. He exists at night.

In the human brain, the night is the subconscious. And so El Pachuco’s the voice inside Henry’s head, who is guiding him to become cool, strong, resistant, proud, and to be himself. Every one of us had a superego. El Pachuco’s a super ego. He is the voice of higher consciousness in Henry’s head.

Henry’s experience as a 19/20-year-old in the play is that he’s going through the process of individuation, which we all do psychologically. As we become ourselves, as we become adults, we have to develop an internal authority. At first, we have parents, teachers, and priests. They become our authorities. We absorb those people and eventually develop an internal authority that speaks to us in our own minds. And that’s El Pachuco. He is the internal authority that is guiding Henry along to a higher consciousness. Eventually, he’s the narrator and the master of ceremonies. He is the raconteur of Zoot Suit. He is the spirit of pachuquismo.

Juveniles don’t rebel, just to rebel. They’re rebelling because that’s part of life. That’s one of the life principles. It’s the motive principle in life, to become a warrior when you’re young. That’s the warrior principle in youth, the pachuco.

What are the meanings behind the clothes of El Pachuco, a black zoot suit with a red shirt, a loincloth, and an all-white zoot suit?

When the Pachuco gets stripped, it’s down to the loincloth. That’s where you have the indigenous aspect. You can’t really strip an Indio. Take the clothes off and we’re down in our natural element.

Red and black are the colors of Tezcatlipoca. The way they represent that in an Aztec and Mayan culture, as in all the cultures in the world, is that red and black are the first colors that the human race ever identified. You see it in petroglyphs and in places around the world. The black and red ink is a sign of this elemental kind of consciousness of being alive and being conscious, which is what the pachuco represents.

White is the twin Quetzalcóatl. You have the magic twins in Aztec/Mayan culture, Tezcatlipoca and Quetzalcóatl. If El Pachuco, in red and black is Tezcatlipoca, then El Pachuco in white is Quetzalcóatl. He’s the feathered serpent. He’s the other side. They’re like night and day. They match each other.

I wanted to show this dynamic in the film. When Henry gets out of prison, he is at a point of beginning again. So, when he meets El Pachuco, he’s in Quetzalcóatl white garb. Henry’s starting out again. But of course, his life doesn’t really change, so it goes back to black and red.

It’s the play of the two magic twins. If you want to know more about it, read Popol Vuh. Popol Vuh is one of the inspirations for this symbolism. It’s not just in my work, it’s in the work of Robert Rodriguez and a number of other playwrights that use this symbolism. We are all into pre-Columbian ideals.

Why was it important to have multiple possible endings for Henry?

My plays have always been about reality and the nature of reality. There isn’t just one reality. We’re talking about an ending, with no one definitive way to look at it. You can be negative. You can be positive. On the other hand, what it does is question the notion of reality. It has to be looked at it from different viewpoints. Remember, there were twelve guys that went to prison, but twenty-two guys that were in the gang were put on trial.

On the one hand, there were people that went back to prison. Henry went back to prison. He barely survived. On the other hand, others went back into the service, and others got educated. Some of the guys got married and had grandchildren. They were grandfathers when I met them. I wanted to emphasize that there were many ways to look at this.

Zoot Suit’s Impact and Legacy:

How did American Latino filmmakers react to Zoot Suit?

It influenced Chicano filmmakers. Unfortunately, they haven’t had the opportunities that they need in order to get their work seen. But there isn’t a single Chicano that hasn’t in some way acknowledged the importance of Zoot Suit.

Do any particular Chicano filmmakers come to mind?

Robert Rodriguez. He’s a good friend of mine. He’s tremendously successful, brilliant, and a great filmmaker. Robert’s been very respectful towards me. Inviting me to be on his network. I really appreciate that coming from a younger filmmaker these days.

What was the reaction to Zoot Suit from Mexican filmmakers?

Zoot Suit had a tremendous impact in Mexico. I was in Mexico when Zoot Suit came out in the early 1980s. A lot of the young filmmakers that have become famous in Hollywood saw it and were inspired by it, as well as some of the older filmmakers.

Which Mexican filmmakers enjoyed Zoot Suit?

As a matter of fact, I learned that Emilio “El Indio” Fernandez really enjoyed Zoot Suit. When I was making La Bamba I wanted Emilio to be in my movie. He was at the end of his career. Emilio was a movie star and a tremendous director in the 1940s. He’s an icon and also the actor that the Oscar statue was designed after.

When I was casting La Bamba, I figured that I’d offer Emilio a cameo. He was interested in doing it. Unfortunately, he had an accident that eventually led to his death. He wasn’t going to be able to make the movie.

Gabriel Figueroa, the great cinematographer also liked the movie. So did the young filmmakers like Emmanuel Lubezki, an award-winning cinematographer. He’s a genius and a great cinematographer. Also Guillermo Navarro, a cinematographer who I work with, Alfonso Cuarón, and Guillermo del Toro. I met them all when they were just starting out in their careers.

Zoot Suit was on everybody’s mind at the time. It was an inspiration for Mexico, to a whole generation. They carried their own careers and talents to new heights in Hollywood, which I’m very happy to see.

How does it feel to have Zoot Suit recently celebrate its 40th anniversary?

Well, 40 years is a long time. But Hollywood is really only a little more than 100 years old. Certainly, the studio system that we all know started about 1918, 1919, 1920. Chaplin was filming in the nineteens but got going in the twenties. So to have a film that’s 40 years old, in that context, is very special to me.

I can see how in other films that as they get older, you can see this dating process that happens. That inevitably, I suppose will happen to Zoot Suit and La Bamba. But they seem to be surviving well thus far. My style has always been to cook a chicken in its own juices. It’s contained within its own reality. And Zoot Suit doesn’t look at the outside world, it’s looking within, at the Aquarius theatre. That reality will always be its referential reality. That will keep it fresh.

Zoot Suit was recently added to the National Film Registry. How does it feel to have it a part of the registry alongside your other film La Bamba?

Zoot Suit was recently added to the National Film Registry. How does it feel to have it a part of the registry alongside your other film La Bamba?

It’s an honor. I have three films in the National Film Registry, which is unusual. One is I am Joaquin, my first film, is a 22-minute short film based on the Corky Gonzales poem “I am Joaquin”. We did this as a slideshow with El Teatro Campesino. That came out in 1970. We created it in 1969. I learned the rudimentary aspects of filmmaking. Then Zoot Suit was inducted. Then La Bamba.

It’s important to leave markers. These are like steps on a ladder to be inspired to climb higher.

The one thing that is lovely about film, is it’s forever. You film it and there it is. I’m happy to say that my films seemed to find new fans in each new generation. Even if they weren’t born when the film was created, they can still relate to it. And that’s one of the wonderful things about film.

La Bamba celebrated its 40th anniversary this year. What do you see in the film that has contributed to its continuing popularity?

La Bamba is a story between two brothers. A Cain and Abel story. It’s really the story of the magic twins. What really keeps it fresh is rock and roll. Ritchie’s music had a wonderful quality. It’s like the swing music in the pachuco era. There’s something universal about music and something eternal about music that when it becomes a hit, it’s because there are some really cosmic vibes in it.

The importance of storytelling and activism:

Why was it important for you to write about the Mexican American and Chicano experience as a form of activism?

Because it hadn’t been dealt with at all. I went to American schools and there was nothing really of Mexican history whatsoever. California history was reduced down to one of the missions you went to visit in fourth grade. Beyond that, there was really nothing, no information whatsoever, no heroes, nothing you could relate to.

I was interested in the theater, I loved the theater, and I enjoyed reading about other people’s cultures and other people’s heroes. There weren’t too many African American, or Asian heroes either. They were all Europeans and or white people.

So I figured, I can help by filling up a gap. I also found that our culture was very rich. It was laying there, all over the place. Nobody was using it. It’s like finding gold scattered all over the ground. I figured, “Oh my God. Let me just tap into our culture and tell the story that I know.” That became the source of my material.

How essential is storytelling in our modern world?

We need storytellers. We need people to continue to retell the human story in a way that includes more people. That’s more fair and honest about other people, about all of us. We need to be able to speak across lines. There are a lot of lines that have been crossed in our time and more will become be crossed as we go, such as gender lines, racial lines, and cultural lines. It’s not just a binary reality anymore.

What do you see as a major challenge that arises from racism?

Racism is an all-enveloping condition. It’s there in human beings and manifests in our social interchanges. It’s there in the laws that people concocted to this day about voting and other things. We’re always going to be wrestling with the whole idea of the other. It’s the tribal consciousness that exists in human beings. We have a long way to go.

How do you see the growth of multiculturalism impacting America?

I think as Americans, we have to be conscious of this, that what Mexico represents is not just a race. We call ourselves La Raza (Spanish for the people). But we’re far from a single Raza (Spanish for race).

To begin with, we had so many tribes with more diverse languages than most places on earth, right within the confines of so-called Mexico. The melting pot started between those tribes, but also with Europeans and all the peoples of the world, from Africa and Asia. What you got is the beginning of a new kind of meld in the human race. Its people still using old terms to try to define us.

That process is overtaking the United States as well. We’re bringing down barriers to racism in this country from intermarrying. Their kids are going to be multiracial and their kids are going to be multicultural, whether people like it or not. God bless them. Multiculturalism is part of the America of human sophistication. The more cultures that we can appreciate and understand, the more sophisticated we are. And ultimately, the better human beings we become.

In that sense, the process that has been in Mexico for the last 500 years, is influencing what’s happening here in the United States. That’s why a lot of people are trying to freeze the border and close it off. Not because they fear Mexicans. It’s because they fear the melting pot that’s happening. They want to keep a position of privilege for themselves. What they don’t realize is that the privilege of the future is the privilege to be part of the human race, the whole human race, not just one segment of it. That will be the power, the brilliance, and the genius of new Americans as they begin to evolve.

We should be aware of the whole world, about every aspect of the human race, cultures, and history of Asia, Europe, Africa, and the Americas. But there isn’t enough information out there about the native peoples in this part of the hemisphere. We have a long way to go.